Estimated Reading Time: 30 mins (5667 words)

The most memorable characters in fiction aren’t simply assembled from checklists—they’re developed from the inside out, revealing themselves layer by layer as their stories unfold.

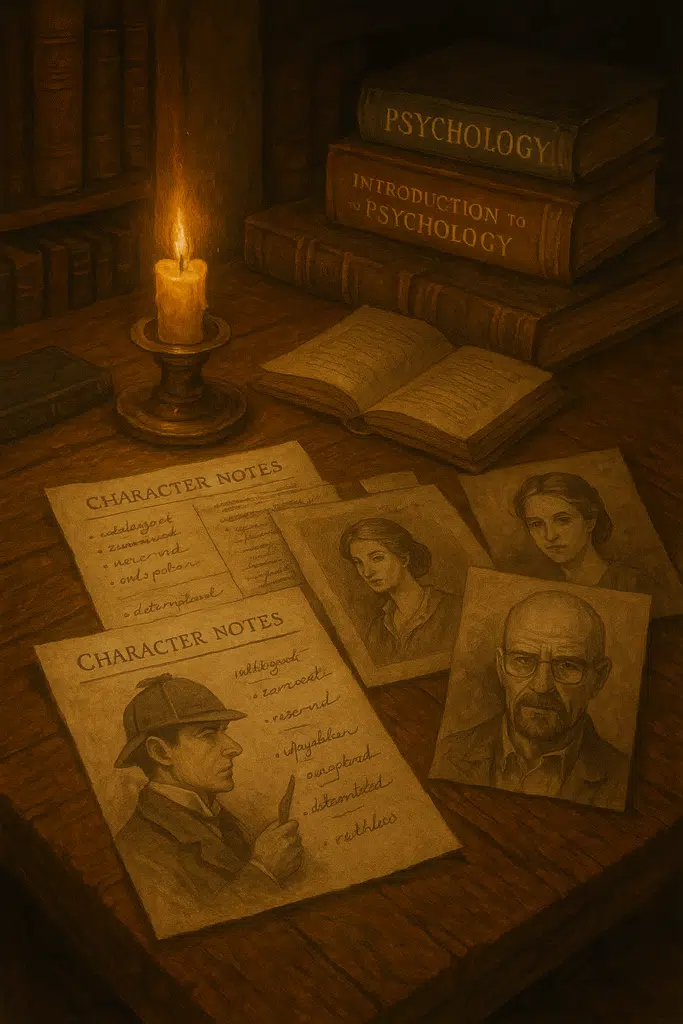

Behind every Elizabeth Bennet, Atticus Finch, or Walter White stands a framework of psychological complexity that transcends their surface attributes. These characters feel real because they struggle with internal contradictions, shifting desires, and the gap between who they believe themselves to be and who they truly are.

Many character templates fall short by focusing exclusively on demographic details and personality traits without exploring how these elements interact under pressure. The magic happens not in listing a character’s features but in understanding how those features transform when tested. A character’s height is just a measurement until we see how it shapes their confidence in crowded rooms; their hometown merely geography until we understand how it molded their values and fears.

When we develop characters through psychological tension rather than static attributes, we create people who breathe and evolve on the page. Their decisions feel inevitable yet surprising—the hallmark of authentic characterization. The most powerful character development doesn’t just tell us who someone is; it reveals who they become when everything they believe about themselves is challenged.

Creating authentic characters goes deeper than checking boxes on a template. The most memorable fictional people evolve through psychological tension and transformation, revealing their true nature when facing meaningful challenges.

- Dig beneath demographic details: While physical traits and basic demographics create a foundation, memorable characters emerge when you understand what these details mean to them — how their height affects their confidence or how their hometown shaped their worldview.

- Craft motivation that shifts under pressure: The most compelling characters don’t just want something; they struggle with competing desires that force difficult choices. Show what happens when their stated motivation conflicts with their deeper, perhaps unacknowledged needs.

- Build a psychological toolbox, not just traits: Instead of listing static personality traits, develop a character’s coping mechanisms, defense strategies, and thinking patterns that both serve and sabotage them throughout their journey.

- Develop relationships that challenge identity: A character’s interactions reveal who they truly are, especially when relationships force them to confront aspects of themselves they’ve avoided or denied.

- Design pressure points, not just flaws: Rather than assigning generic weaknesses, identify the specific circumstances that break your character’s normal functioning and expose their authentic self.

- Map the gap between self-perception and reality: The distance between who your character believes they are versus who they actually are creates the tension that drives meaningful growth.

Character development isn’t about filling in blanks on a template — it’s about creating a psychological framework that allows your character to evolve organically through your story. Let’s explore how to build characters whose inner worlds feel as real and complex as our own.

The Psychology Behind Memorable Characters

Why demographic details alone create forgettable people

Characters built solely from demographic information—age, height, occupation, hometown—rarely linger in readers’ minds after the final page. These surface-level attributes function like a driver’s license: they identify a person but reveal nothing about who they truly are beneath these labels. A 35-year-old accountant from Chicago might appear in countless stories, yet these facts alone tell us nothing about what makes this particular accountant unique, complex, or worth following for hundreds of pages.

When writers rely too heavily on demographic shorthand, they create what psychologists might call “thin-slice” characters—figures we recognize but cannot connect with emotionally. These characters become interchangeable pieces on the narrative chessboard, moving according to plot requirements rather than internal compass. The accountant becomes merely “the accountant,” a function rather than a person with hopes, fears, and contradictions that transcend his job title.

Consider how different Patrick Bateman from “American Psycho” would be if Ellis had only provided his demographic details without the psychological paradoxes that make him simultaneously repulsive and fascinating. His status as a wealthy Wall Street executive isn’t what makes him memorable—it’s the horrifying contrast between his meticulous attention to social conformity and his inner violence, his desperate need for recognition and his fundamental emptiness.

The difference between characters readers remember vs. forget

The characters that haunt us long after we’ve finished their stories share a crucial quality: psychological authenticity. These memorable figures possess inner workings that follow recognizable human patterns while surprising us with their individual expressions of universal struggles. They aren’t merely consistent; they’re consistently complex in ways that mirror real human psychology.

Forgettable characters typically demonstrate one of two common flaws: either they’re psychologically inconsistent, acting out of character to serve plot requirements, or they’re one-dimensional, representing a single attribute without the contradictions that define actual people. The memorable character, by contrast, contains multitudes that make sense together even when they seem to conflict.

Think of Severus Snape from the Harry Potter series. What makes Snape unforgettable isn’t his role as Potions Master or his physical description, but the psychological complexity revealed as his apparently contradictory behaviors gradually cohere into a portrait of a man torn between resentment and love, between past wounds and present choices. His actions become both surprising and inevitable because they emerge from a fully realized psychological framework rather than convenient plot requirements.

Memorable characters also tend to change in ways that feel earned rather than imposed. Their transformations arise organically from the collision between their established psychological patterns and the challenges they face. They struggle visibly with their choices, making their eventual evolution deeply satisfying rather than merely expected.

Beyond the Checklist Approach

When “strong female character” becomes an empty label

The “strong female character” represents perhaps the most evident example of how checklist thinking creates hollow characterization. Originally intended to promote more dimensional female representation, the term has ironically become shorthand for characters who often lack psychological complexity. The result is frequently a collection of surface-level traits—physical toughness, sarcastic quips, combat skills—without the vulnerabilities, contradictions, and inner conflicts that make strength meaningful.

A truly strong character—regardless of gender—demonstrates psychological resilience while grappling with weaknesses, makes difficult choices while questioning their own motives, and evolves through failing as much as succeeding. When writers apply the “strong female character” label without this psychological underpinning, they create figures who may kick down doors impressively but never reveal what drives them, what frightens them, or how they reconcile their power with their humanity.

Compare the psychological richness of Frances McDormand’s Mildred Hayes in “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri” with more formulaic “strong female characters.” Mildred’s strength doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it emerges from grief, guilt, and rage. Her power feels earned precisely because we understand its psychological origins and cost. She isn’t strong despite her brokenness; her particular kind of strength exists because of it.

The danger of trait-collecting without psychological integration

Many character development approaches encourage writers to compile exhaustive trait inventories—likes, dislikes, quirks, talents, preferences—that create the illusion of depth without actually achieving it. The fundamental problem with trait-collecting is not the traits themselves but the lack of psychological integration that explains why these particular traits coexist within one person and how they influence each other under pressure.

A character who loves jazz, fears heights, excels at chess, and habitually cracks knuckles may seem well-defined on paper, but these attributes remain merely decorative unless they connect to deeper psychological patterns. Does their love of jazz reflect an appreciation for improvisation that extends to how they handle life’s uncertainties? Does their fear of heights relate to a formative experience that shaped their approach to risk in all areas? Without this integration, traits become random accessories rather than revealing expressions of a coherent inner reality.

The most compelling characters possess traits that both reinforce and contradict each other in psychologically credible ways. Their attributes don’t simply coexist—they interact, creating internal tensions that drive behavior. A character’s ambition might constantly battle with their fear of success; their generosity might mask a need for control. These psychological dynamics transform a collection of traits into a living, breathing person whose choices feel both surprising and inevitable.

The Inner-Outer Framework

Physical traits as windows to psychological reality

Physical characteristics become meaningful when they serve as portals into a character’s psychological landscape rather than mere visual identifiers. A character’s tall stature isn’t just a physical measurement—it’s a lifelong influence on how others perceive them and how they navigate the world. Perhaps they’ve learned to slouch to avoid drawing attention, revealing deep-seated discomfort with standing out. Or maybe they’ve embraced their height, developing a commanding presence that masks inner uncertainty about deserving the authority others automatically grant them.

Even seemingly minor physical attributes can illuminate profound psychological truths when writers explore their emotional impact. A character’s unusual eye color might have subjected them to childhood teasing that fostered resilience or insecurity. A distinctive scar might serve as a daily reminder of a moment when their life changed direction, becoming both a physical mark and a psychological boundary between who they were before and after the injury.

The power of physical traits lies not in their objective description but in their subjective significance to the character. Jane Austen demonstrates this brilliantly when she has Mr. Darcy find Elizabeth Bennet’s “fine eyes” beautiful despite her otherwise “barely tolerable” appearance—revealing more about Darcy’s emerging affection and psychological state than about Elizabeth’s actual appearance.

How external details reflect internal truths

External details—from clothing choices to living spaces—function most effectively when they externalize internal realities rather than simply establishing setting or period. A meticulously organized desk reflects more than tidiness; it might reveal a character’s attempt to impose order on a life that feels dangerously chaotic, or demonstrate their belief that maintaining perfect external control will prevent internal collapse.

A character’s environment often functions as psychological externalization—the physical manifestation of their inner world. Miss Havisham’s decaying wedding feast in “Great Expectations” isn’t merely atmospheric; it’s the perfect physical expression of her psychological state—time arrested at the moment of her greatest pain, deteriorating while she clings to it. The room tells us everything about her before she speaks a word.

Even seemingly practical external choices carry psychological weight. A character who drives an expensive car but lives in a modest apartment might be revealing profoundly different priorities than someone making the opposite choice. Their clothing might demonstrate conformity, rebellion, self-protection, or attraction-seeking. These details work hardest when they don’t just decorate the character but decrypt them—offering readers subtle clues about the internal forces driving external behaviors.

Excavating Meaningful Backstory

Turning life events into psychological imprints

The most effective character backstories translate formative experiences into lasting psychological imprints rather than simply cataloging past events. A character isn’t shaped by the mere fact that their parents divorced when they were twelve; they’re shaped by how they interpreted that event, what beliefs about relationships it fostered, what coping mechanisms they developed in response, and how those adaptations continue to influence their adult choices.

When excavating meaningful backstory, the critical question isn’t just “What happened?” but “How did this event shape this particular character’s understanding of themselves and the world?” Two siblings might experience the same parental divorce entirely differently—one developing fear of abandonment that manifests as clingy relationship behavior, the other building walls against emotional dependency. The event matters less than the psychological framework it created.

The most powerful backstory elements aren’t necessarily the most dramatic. Sometimes quiet disappointments shape psychology more profoundly than spectacular traumas. A character whose early artistic efforts were consistently dismissed might develop a deeper psychological wound than one who experienced a more obviously traumatic but isolated incident. The chronic, formative experiences that established a character’s core beliefs about themselves often exert more influence than exceptional moments of crisis.

Identifying formative moments that shaped worldview

Formative moments represent the psychological turning points that established a character’s fundamental assumptions about how the world works and their place within it. These critical junctures typically occur when characters are vulnerable—particularly in childhood, adolescence, or during adult periods of transition—and tend to embed lasting lessons that may or may not be accurate.

To identify truly formative moments, look for experiences that forced the character to draw conclusions about fundamental questions: Is the world basically safe or dangerous? Are people generally trustworthy or threatening? Is vulnerability rewarded or punished? Am I essentially worthy or unworthy? These early “answers” become the foundation of a character’s worldview and the lens through which they interpret subsequent experiences.

The moments that most powerfully shape worldview often involve the character’s primary relationships and earliest experiences of success, failure, betrayal, or validation. A child who learned that emotional expression was met with rejection might develop a worldview built around self-containment. A teenager who discovered their intellectual gifts brought social ostracism might build an identity that simultaneously values and resents intelligence. These formative interpretations matter more than the events themselves because they establish the filters through which the character will process everything that follows.

The Contradictions That Breathe Life

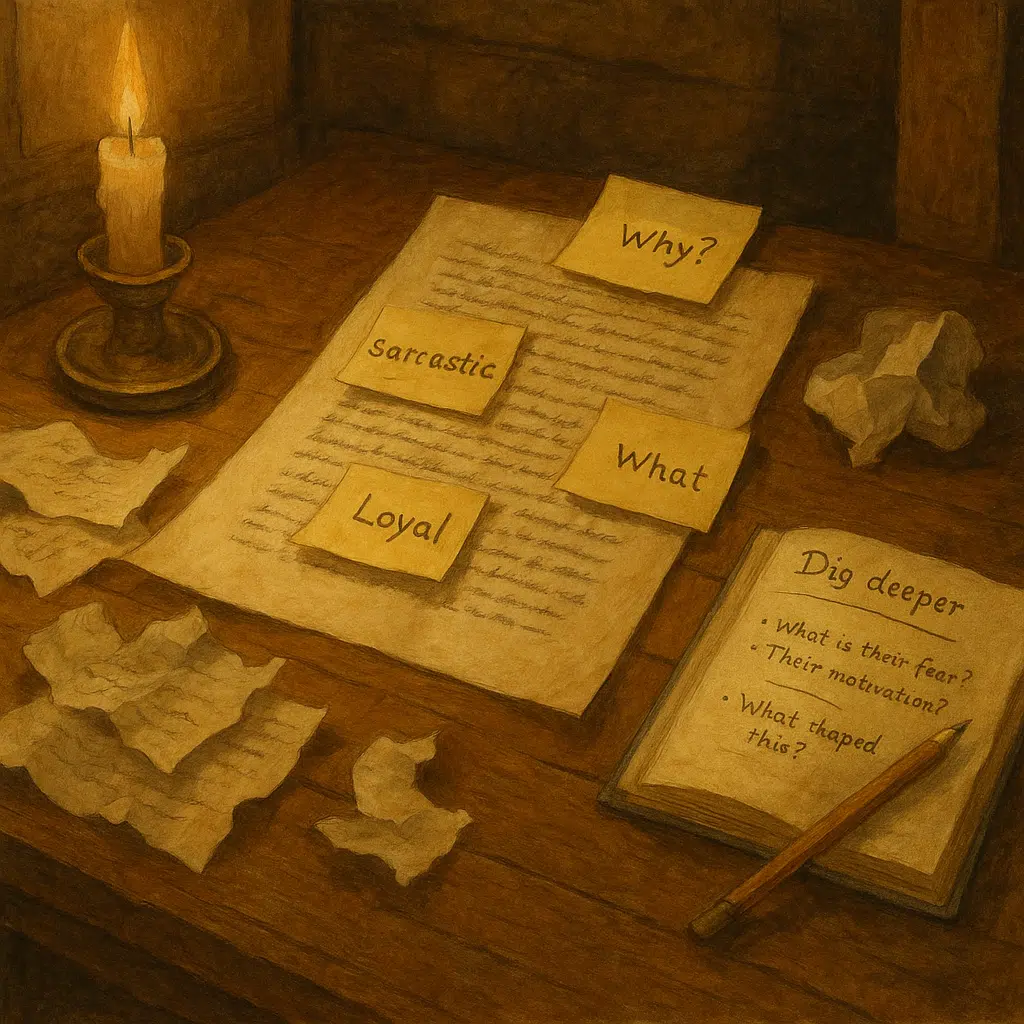

Harnessing the power of competing desires

The most vivid characters aren’t driven by single desires but torn between competing wants that create internal tension even before external obstacles arise. This psychological tug-of-war forms the heart of authentic characterization, creating figures who struggle not just against outside forces but against their own contradictory impulses—a fundamentally human experience that readers instantly recognize.

Consider a detective who desperately wants to solve a case while simultaneously fearing what the truth will reveal—perhaps about a colleague, a loved one, or herself. This internal contradiction creates compelling tension in every investigative choice she makes. Should she follow a threatening lead or avoid it? Each option satisfies one desire while frustrating another, forcing her to constantly prioritize competing values in ways that reveal character more powerfully than any physical description or personality trait could.

The most productive character contradictions emerge from core values or needs that directly conflict. A character might crave both independence and connection, honesty and acceptance, achievement and ethical integrity. When circumstances force them to choose between these competing desires—particularly when both options represent something genuinely important to them—they reveal their true priorities and values. These moments of choice, driven by internal contradiction rather than just external pressure, form the bedrock of authentic character revelation.

When wants and needs create character tension

The gap between what characters consciously want versus what they unconsciously need creates particularly rich psychological territory. Characters who pursue goals that won’t actually fulfill their deeper needs operate under a form of dramatic irony—the reader often recognizes sooner than the character that achieving their stated desire won’t resolve their fundamental wound or satisfy their underlying hunger.

A character might pursue wealth believing it will earn respect, only to discover that financial success without integrity leaves them more hollow than before. Another might chase romantic relationships convinced that partnership will heal their insecurity, only to find that external validation can’t substitute for internal self-acceptance. This misalignment between conscious wants and unconscious needs drives many compelling character arcs, with growth often involving the painful recognition that they’ve been seeking fulfillment in the wrong places.

This tension becomes especially powerful when fulfilling the character’s conscious want would actually prevent them from addressing their unconscious need. The businessman who believes success will earn his father’s approval might need to abandon that pursuit to confront his deeper need for self-acceptance. The perfectionist who wants to control every outcome might need to embrace vulnerability to satisfy her deeper need for genuine connection. These characters face not just external obstacles but the ultimately more challenging task of recognizing that their carefully constructed goals may be preventing them from obtaining what they truly need.

Motivation That Evolves Under Pressure

Why single-minded characters feel artificial

Characters driven by single, unwavering motivations rarely ring true because they lack the psychological flexibility that defines real human behavior. People adapt their motivations as circumstances change, as they receive new information, and as they experience the consequences of their choices. A character who pursues the same goal with the same intensity regardless of what happens around them feels mechanical rather than human—a plot function rather than a person.

Even characters with powerful driving motivations—revenge, justice, love—demonstrate psychological complexity when their commitment to these goals fluctuates under pressure. Ahab’s monomaniacal pursuit of the white whale feels authentic precisely because Melville shows the captain’s momentary doubts, his awareness of the destruction his obsession causes, and his inability to choose a different path despite this knowledge. Without these glimpses of psychological struggle, Ahab would be merely a symbolic figure rather than a tragically human one.

The most compelling characters don’t abandon their core motivations entirely but experience shifts in how they understand and pursue their goals as their stories unfold. They question themselves, reconsider their methods, and sometimes discover that achieving their original objective requires a fundamentally different approach than they initially imagined. This evolution feels genuine because it mirrors how real people adapt their goals while maintaining their essential values.

Designing the breaking point for motivation shifts

Every character has psychological breaking points—specific pressures or revelations that force them to reevaluate their motivations and potentially adopt new ones. Identifying these breaking points requires understanding both what the character values most deeply and what assumptions underlie their current motivational framework. When experience challenges those assumptions, motivation naturally shifts in response.

A character motivated by protecting their family might experience a breaking point when they realize their protective actions are actually causing harm to the people they love. A character driven by ambition might reach their breaking point when achieving long-sought success leaves them feeling empty rather than fulfilled. These moments force characters to confront the gap between what they thought would bring satisfaction and what actually does.

The most effective motivation shifts arise when characters face irreconcilable conflicts between different values they hold dear. A character committed to both justice and loyalty reaches a breaking point when these values collide—when pursuing justice would mean betraying someone they love, or remaining loyal would require ignoring a serious wrong. These breaking points don’t feel contrived because they emerge organically from the character’s established value system being tested in ways that reveal its internal contradictions.

From Static Traits to Dynamic Psychology

Building a character’s thinking patterns and blind spots

Rather than listing fixed personality traits, developing a character’s characteristic thinking patterns creates a psychological framework that generates consistent yet evolving behavior across different situations. These cognitive patterns—how they process information, what they automatically notice or overlook, which explanations they reach for first—form the architecture of their personality and drive their responses to new challenges.

Some characters habitually look for threats, scanning each situation for potential dangers and preparing for worst-case scenarios. Others automatically search for points of connection, focusing on relationship possibilities rather than risks. Some consistently attribute success to their efforts and failure to external circumstances, while others do the opposite. These thinking patterns don’t determine every response but create tendencies that make characters both recognizable and capable of surprising us when circumstances push them beyond their typical cognitive frameworks.

Equally important are a character’s psychological blind spots—the aspects of themselves and their situations they consistently fail to perceive accurately. A character might be keenly insightful about others’ motivations while remaining oblivious to their own. Another might accurately assess practical problems while misreading emotional cues. These cognitive blind spots create natural opportunities for character growth while explaining why intelligent characters sometimes make decisions that seem obviously flawed to readers who see what they cannot.

Developing signature coping mechanisms and defense strategies

Every compelling character possesses signature ways of handling stress, threat, and emotional discomfort that reveal their psychological architecture more clearly than their behavior under optimal conditions. These coping mechanisms evolve from early experiences and become so automatic that characters often employ them unconsciously, only recognizing their patterns when these strategies fail them or create unexpected consequences.

Some characters reflexively use humor to defuse tension, while others withdraw to process emotions privately. Some attack problems head-on, while others analyze extensively before acting. Some seek connection when distressed, while others isolate themselves. These consistent patterns help readers understand how a character will likely respond to new challenges while allowing for growth when familiar coping strategies prove inadequate for unprecedented situations.

Defense mechanisms—the psychological strategies characters use to protect themselves from uncomfortable truths or feelings—provide particularly rich material for character development. A character who relies on intellectualization might analyze emotions rather than feeling them. One who employs projection might attribute their own unacknowledged traits to others. Another might use compartmentalization to separate conflicting aspects of their experience. These defense strategies simultaneously protect and limit characters, creating both stability and the potential for meaningful growth when circumstances force them to develop more effective responses.

Creating Authentic Pressure Points

The specific circumstances that reveal true character

Generic challenges reveal little about specific characters. The most illuminating pressure points are precisely calibrated to target a particular character’s psychological vulnerabilities, forcing them to confront aspects of themselves they’ve avoided or denied. These tailored challenges create situations where the character’s usual coping mechanisms prove inadequate, requiring them to either evolve or fail in ways that reveal their core values and limitations.

For a character who maintains control through careful planning, the most revealing pressure comes not from any difficulty but specifically from chaos that defies preparation. For someone who builds identity around intellectual capability, the most exposing challenge involves problems that cannot be solved through analysis alone. For a character who avoids emotional intimacy, the most potent pressure point comes from situations demanding vulnerable connection.

The circumstances that most authentically reveal character often involve forced choices between competing values the character holds dear. When a character who values both honesty and loyalty must choose between telling a painful truth or protecting someone they love, their decision reveals which principle ultimately guides them when both cannot be satisfied. These value conflicts expose character more profoundly than external dangers because they force characters to demonstrate—through action—what they truly prioritize when they cannot have everything they value.

How to design tailored challenges that force growth

Effective character challenges target the precise gap between who characters believe themselves to be and who they actually are or could become. This gap creates productive discomfort that drives meaningful change rather than merely testing skills or strength. A character who prides themselves on independence might need challenges that force them to accept help, revealing both the limitations of self-sufficiency and their capacity for reciprocal relationships they’ve previously avoided.

The most growth-inducing challenges often require characters to develop capabilities that directly contradict their self-concept or habitual responses. A character defined by caution might need situations demanding bold action; one accustomed to solving problems alone might need challenges requiring collaboration. These experiences don’t merely test characters but transform them by demonstrating that they possess capacities they’ve denied or neglected.

Designing challenges that force authentic growth requires understanding both what the character fears most and what latent strengths they possess but haven’t acknowledged. The ideal challenge places them in situations where avoiding their fear becomes more painful than facing it, while simultaneously providing opportunities to discover capabilities they didn’t know they had. This combination—maximum psychological pressure paired with potential for new self-discovery—creates the conditions for believable transformation rather than simplistic “leveling up” that characterizes less psychologically sophisticated narratives.

The Self-Perception Gap

Characters who don’t know themselves

The distance between how characters see themselves and who they actually are creates one of the richest sources of psychological tension in fiction. These self-perception gaps generate both internal conflict (as characters struggle to maintain self-images contradicted by their behavior) and external conflict (as others respond to who characters actually are rather than who they believe themselves to be).

Some characters consistently overestimate their capabilities, creating a gap between their confidence and competence that drives both comedy and tragedy. Others underestimate themselves, failing to recognize strengths that readers can clearly see. Some believe themselves motivated by noble principles while actually driven by unacknowledged selfish desires. Others consider themselves fundamentally flawed while demonstrating virtues they cannot acknowledge.

These self-perception gaps often originate in formative experiences that established distorted self-views the character has never questioned. A child told repeatedly that they’re selfish might develop a compensatory self-image as exceptionally generous, even when their actions don’t support this view. Another raised with excessive praise might maintain an inflated self-concept despite regular evidence of their limitations. These persistent self-misperceptions create both consistency (as characters struggle to maintain their established self-view) and opportunity for growth (when circumstances finally force them to confront the reality of who they are).

Using dramatic irony to highlight internal conflict

Dramatic irony—when readers understand something about a character that the character themselves doesn’t recognize—transforms self-perception gaps from abstract psychological concepts into powerful narrative engines. Readers who see what characters cannot about themselves experience the tension of waiting for inevitable self-discovery, creating engagement that propels the story forward.

This technique works most effectively when readers receive clear indicators of the character’s actual motives, capabilities, or impact while also understanding why the character maintains their distorted self-perception. We might see that a character who considers himself a protective figure actually causes harm through his controlling behavior, while also understanding that his self-image as protector stems from early experiences that make this self-recognition threatening. This multi-layered awareness creates both empathy for the character’s blindness and anticipation of the reckoning that must eventually come.

The gap between character self-perception and reality creates particularly compelling tension when characters make decisions based on their distorted self-understanding. A character who believes herself fundamentally unworthy of love might sabotage promising relationships to maintain this familiar self-concept, even as readers recognize her inherent worthiness. Another who sees himself as consistently rational might make wildly emotional decisions while constructing elaborate justifications to maintain his self-image. These contradictions between self-perception and behavior create the authentically flawed characters that readers recognize as fundamentally human.

Relationship Dynamics That Force Change

Mirror characters who reflect uncomfortable truths

Mirror characters serve as powerful catalysts for growth by reflecting aspects of the protagonist that they’ve denied, suppressed, or failed to recognize in themselves. Unlike simple foils who merely contrast with the main character, effective mirror characters embody traits or choices that directly challenge the protagonist’s self-perception, forcing them to confront uncomfortable similarities they’ve been unwilling to acknowledge.

A protagonist who abhors manipulation might encounter a mirror character who uses similar tactics but for different ends, exposing the protagonist’s unacknowledged tendencies to influence others. A character who considers themselves fundamentally selfless might meet someone whose extreme self-sacrifice reveals the hidden control mechanisms in the protagonist’s apparent generosity. These reflections work because they don’t introduce entirely new insights but rather illuminate what was already present but denied.

The most effective mirror characters don’t function as simple object lessons but engage in authentic relationships with the protagonist that make avoiding self-recognition increasingly difficult. When a character genuinely cares about someone who reflects their disowned qualities, they cannot simply reject what they see without also rejecting the relationship. This emotional investment creates stakes for self-awareness that purely intellectual confrontation cannot achieve, making change both more necessary and more challenging.

Designing interactions that challenge identity

Relationships force character growth most effectively when they create situations where maintaining established identity becomes more painful than changing. A character who defines herself through independence might form a connection that makes isolation more unbearable than the vulnerability she fears. Another who maintains rigid moral certainty might develop a relationship with someone whose complex circumstances defies his black-and-white categorization, forcing him to develop more nuanced ethical thinking.

The relationships that most powerfully challenge identity combine acceptance and confrontation—the character feels truly seen and valued while simultaneously facing aspects of themselves they’ve avoided acknowledging. This combination creates psychological safety for change while providing the uncomfortable friction necessary to motivate it. When characters feel both loved and challenged within the same relationship, they often find the courage to examine long-held beliefs about who they are and who they can become.

Particularly transformative relationships often involve characters operating from different identity frameworks entirely. A character who organizes identity around achievement might form a meaningful connection with someone who values presence over accomplishment, offering an alternative model they’ve never considered viable. Another who builds self-worth on helping others might develop a relationship with someone who demonstrates self-acceptance without constant service, challenging their belief that value must be earned through perpetual giving.

Evolution Through Crisis

Mapping the transformation catalyst

Character transformation rarely occurs gradually—it typically requires crisis points that make maintaining old patterns impossible. These transformation catalysts create circumstances where characters must either evolve or face consequences more painful than the discomfort of change. Effective catalysts typically combine maximum external pressure with internal recognition, creating both the necessity and possibility of authentic transformation.

The most powerful transformation catalysts target the specific psychological patterns that have both protected and limited a particular character. For someone whose identity centers on intellectual control, the catalyst often involves a situation that cannot be analyzed or understood within their existing mental frameworks. For a character who avoids emotional vulnerability at all costs, the catalyst typically creates circumstances where continued emotional withholding would cause unbearable loss.

Transformation catalysts work most effectively when they create what psychologists call “optimal discomfort”—enough destabilization to make change necessary but not so much that the character becomes completely overwhelmed. Too little pressure allows characters to maintain existing patterns; too much triggers extreme defensive responses that prevent growth. The ideal catalyst creates precisely the level of discomfort that makes developing new capabilities feel like the most viable option, even for characters strongly resistant to change.

How external conflict triggers internal growth

External conflicts serve as the visible manifestation of internal psychological struggles, creating circumstances that force characters to confront limitations they could otherwise continue to avoid. The most effective external conflicts don’t simply test characters’ existing strengths but specifically challenge the assumptions, defenses, and coping mechanisms that have defined their approach to life.

A character who has always equated worth with achievement might face external circumstances that make success impossible through familiar methods, forcing them to find value beyond accomplishment. Another who has avoided intimacy through constant movement might encounter external restrictions on their mobility, requiring them to develop connection skills they’ve never needed before. These external challenges function less as obstacles to overcome than as invitations to develop entirely new ways of being.

The relationship between external conflict and internal growth becomes most powerful when the external challenge systematically dismantles the character’s existing psychological framework while simultaneously creating opportunities to develop new capacities. A character might lose everything that previously defined their identity—career, relationship, status, health—while discovering capabilities for resilience, connection, or creativity they never knew they possessed. This simultaneous deconstructing and rebuilding creates transformation that feels both devastating and ultimately generous, breaking down limiting patterns while revealing new possibilities.

The Template as Framework, Not Formula

Customizing psychological development tools

The most effective character development approaches recognize that while certain psychological principles apply broadly, their expressions vary infinitely based on individual characters’ specific histories, contexts, and internal landscapes. Rather than applying formulaic templates that produce cookie-cutter characters, skilled writers adapt psychological frameworks to illuminate the particular tensions and growth trajectories that make sense for each unique character.

Different characters require different psychological development tools. A character shaped by early abandonment will demonstrate different patterns than one influenced by excessive control, even if both struggle with intimacy as adults. A character raised in extreme poverty will process achievement differently than one who grew up with abundance but emotional neglect. These specifics matter—they transform abstract psychological concepts into the textured, particular inner worlds that make characters feel authentic rather than assembled from components.

Customizing psychological tools requires deep familiarity with the character’s core wounds, beliefs, values, and defensive strategies. Once these foundations are established, writers can select the psychological frameworks that best illuminate this specific character’s inner landscape. A character dealing primarily with identity questions might benefit from developmental psychology approaches, while another struggling with competing loyalties might be better understood through moral psychology frameworks. This targeted application creates psychological portraits that feel both coherent and unique.

Building your own character development approach

Rather than adopting any single psychological template wholesale, the most sophisticated character developers create personalized approaches that reflect their unique interests, insights, and storytelling priorities. Some writers naturally gravitate toward exploring moral development, while others focus on attachment patterns or identity formation. These preferences aren’t limitations but specializations that allow writers to develop particular psychological depth in the dimensions that most interest them.

Building your own approach begins with identifying the psychological questions that consistently fascinate you. Do you find yourself drawn to exploring how people reconcile contradictory aspects of themselves? How they navigate competing loyalties? How they recover from betrayal or loss? These recurring interests often point toward the psychological territories where you’ll create your most insightful character work.

The most effective personalized approaches combine intuitive understanding with structured frameworks, allowing writers to trust their instincts while also checking them against psychological principles. This balance prevents both overly mechanical characterization (following psychological formulas without emotional truth) and purely intuitive character work (which can lack coherence or depth). By developing psychological frameworks that support rather than replace creative intuition, writers create characters who feel simultaneously unique and universal—individuals who embody particular experiences while illuminating broader human truths.

The templates and frameworks we use are merely doorways into our characters’ inner worlds—not their full architecture. As you sit with your characters, listening for the whispers of their contradictions and the echoes of their unspoken fears, you’ll discover that the most profound character development happens in the spaces between your planned notes. Your most memorable characters will ultimately surprise even you, revealing depths you never consciously designed but somehow always knew were there.