Estimated Reading Time: 24 minutes (4473 words)

Every character carries the invisible weight of their past onto the page, long before readers meet them. The most unforgettable characters in fiction aren’t born at the opening sentence – they arrive with histories that have shaped their fears, dreams, and the particular way they see the world. These histories aren’t decorative details to file away in character sheets; they’re the hidden engines of your entire narrative.

The difference between forgettable characters and those who haunt readers long after the story ends often comes down to backstory – not just having one, but crafting one that actively drives the story forward. When a character’s past experiences inform every choice they make, every relationship they form, and every obstacle they face, the result is a narrative that feels inevitable rather than contrived.

Creating these histories isn’t about piling on tragic childhoods or elaborate origin stories. It’s about understanding how the past lives in the present – how old wounds resurface, how learned patterns dictate responses to new challenges, and how buried secrets can explode into current conflicts at precisely the right dramatic moment.

The most powerful backstories don’t just explain who a character is; they create tension around who they might become. They establish patterns your character is destined to either repeat or finally break free from. When readers understand not just what happened to your characters but how those experiences continue to haunt them, every scene becomes charged with deeper significance and possibility.

Character backstories sit at the heart of remarkable fiction, but they’re not merely decorative elements to be filed away. When crafted with intention and revealed strategically, a character’s past becomes an engine that propels your narrative forward and deepens reader investment.

- Treat backstory as plot fuel, not character furniture: Backstories should actively drive present action rather than sitting like static background information. Every significant element from a character’s past should create ripples in their current decisions and relationships.

- Parcel out revelations strategically: Rather than front-loading history in chapter one, reveal backstory in carefully timed moments when they’ll have maximum emotional impact. This creates a dual narrative tension where readers simultaneously wonder what will happen next and what happened before.

- Root motivations in psychological wounds: A character’s deepest drives often stem from unresolved past trauma or formative experiences. Identify the core wound that shapes their worldview and use it to create consistent yet complex reactions to story events.

- Connect past events to present stakes: The most compelling backstories establish patterns that make current conflicts feel inevitable rather than random. Show how your character’s history has set them on a collision course with your story’s central problem.

- Build authentic histories that invite empathy: Even villains have origin stories that made sense to them. Craft pasts that help readers understand a character’s perspective without necessarily excusing their actions.

- Layer in backstory through multiple techniques: Avoid the dreaded info-dump by varying your revelation methods – from dialogue and flashbacks to meaningful objects or setting details that trigger memories.

- Allow backstory to evolve as characters do: A character’s understanding of their own past should shift as they grow. What they once perceived as betrayal might later be recontextualized as protection, creating powerful moments of character development.

The art of compelling backstory lies not just in what happened before page one, but in how those events continue to resonate throughout your narrative. Let’s explore how to craft histories that breathe life into your characters and momentum into your plot.

The Psychology Behind Powerful Backstories

Why some character histories resonate while others fall flat

Character backstories resonate when they feel authentic rather than manufactured. The most compelling histories aren’t collections of random tragic events but cohesive narratives that explain fundamental aspects of who a character has become. When readers encounter Ellen Ripley’s maternal protectiveness in “Aliens,” it resonates because it reflects her backstory of having lost her daughter while in hypersleep. This isn’t merely sad—it’s psychologically transformative.

Characters with flat backstories often suffer from “biographical listing syndrome”—details that exist as character resume points rather than formative experiences. A character whose parents died when they were young only resonates if we understand how that abandonment shaped their ability to form attachments, trust others, or navigate the world. The backstory must create specific psychological consequences that manifest in the character’s present behavior — something we explore more deeply in Creating Authentic Character Profiles.

The most resonant backstories also avoid extremes. While characters who’ve experienced extraordinary trauma or privilege can work, they often connect less effectively than those whose histories contain relatable human experiences—betrayal, disappointment, unexpected kindness, or formative success. These universal emotional touchpoints create bridges of understanding between reader and character.

The connection between past wounds and present choices

Characters are most believable when their decision-making directly reflects their psychological wounding. Someone abandoned as a child may struggle with commitment, either avoiding it entirely or clinging too tightly to relationships. A character betrayed by authority figures might maintain a lifelong suspicion of institutions. These aren’t simplistic one-to-one correlations but complex adaptive behaviors that developed for survival — a topic that overlaps heavily with how players explore identity and safety in roleplay.

This connection between wound and behavior creates a powerful narrative tool: predictable unpredictability. Readers understand why a character makes seemingly irrational choices because they recognize the underlying pattern of self-protection. When Harry Potter instinctively distrusts adults and tries to solve problems without seeking help, readers understand this stems from years of neglect and learning to rely only on himself.

The most sophisticated character development occurs when protagonists gradually recognize these patterns themselves. Their backstory becomes not just explanation for the reader but territory the character must navigate to grow. As they gain awareness of how past wounds dictate present choices, characters gain the power to make different decisions—creating the foundation for meaningful character arcs that feel both surprising and inevitable.

Backstory as Plot Engine

Turning history into forward momentum

Backstory becomes a plot engine when it creates unresolved tensions that demand resolution. Unlike static details that merely explain, dynamic backstories plant time bombs within characters that inevitably detonate during the narrative. These aren’t convenient coincidences but psychological imperatives—the character’s history creates needs, fears, and desires that actively propel them into and through the story’s central conflict.

Consider how Veronica Mars’s backstory—the murder of her best friend, her subsequent ostracism, and her father’s fall from grace—doesn’t simply explain her cynicism but actively drives her to solve mysteries and expose corruption. Her past creates both the skills and the psychological need that propels every investigation — a clear example of story mechanics shaping character motivation. The external plot (solving crimes) seamlessly intertwines with internal motivation (seeking justice she never received).

Effective backstories create specific stakes for characters that extend beyond the general stakes of the plot. When Michael Corleone in “The Godfather” becomes involved in his family’s criminal enterprise—despite his backstory of deliberately distancing himself from it—the tension comes from how this violates his carefully constructed identity. The plot moves forward not just through external pressure but through the gravitational pull of unresolved family history.

When the past refuses to stay buried

The most dynamically plotted stories often feature backstory elements that intrude increasingly into the present narrative. What begins as occasional references or nightmares escalates into physical manifestations, confrontations with people from the past, or the literal uncovering of hidden information. This escalation creates a dual tension: the forward-moving plot and the backward-revealing truth.

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” exemplifies this perfectly—Sethe’s past literally manifests as a ghost whose presence grows more demanding and disruptive. The backstory doesn’t simply inform the present but actively haunts it, forcing confrontation. Similarly, in “Chinatown,” Jake Gittes investigates what seems like a standard case of infidelity only to uncover Evelyn Mulwray’s devastating family secret, which has shaped the entire mystery.

This refusal of the past to remain buried creates compelling narrative momentum because it follows psychological truth: unprocessed trauma demands attention. Characters who have sealed off parts of their history inevitably find those sealed chambers breaking open precisely when they’re most vulnerable or have the most to lose. The story can only resolve when the character finally turns to face what they’ve been running from—making the backstory not just context but climax.

The Art of Strategic Revelation

Parceling out history at moments of maximum impact

The timing of backstory revelations transforms their power — and it’s deeply tied to how readers emotionally experience scenes, as explored in Immersion by Design. Skilled writers withhold key elements of character history until the moment when this information will have maximum emotional or narrative impact. This isn’t about arbitrary secrecy but about understanding how revelations function as emotional turning points within larger narrative arcs.

Consider how J.K. Rowling parcels out Severus Snape’s history across seven Harry Potter books. Each revelation—his childhood friendship with Lily, his love for her, his role as double agent—recalibrates readers’ understanding precisely when it creates maximum tension or pathos. Had these elements been revealed chronologically or all at once, they would have lost their transformative power over both character relationships and reader experience.

Strategic revelation works through careful preparation and meaningful payoff. The backstory element must be subtly seeded through character behaviors, preferences, or reactions that initially seem odd or inconsistent. When the revelation comes, it should function as an “of course” moment that suddenly explains those inconsistencies while simultaneously raising new questions or complications.

Creating dual narrative tension through delayed disclosure

When writers strategically withhold key backstory elements, they create a dual narrative tension: readers are pulled forward by current plot developments while simultaneously being pulled backward by the mystery of the character’s past. This technique works especially well when the protagonist themselves doesn’t fully understand their history or is actively avoiding confronting it.

Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” (adapted as the film “Arrival”) masterfully employs this technique, gradually revealing that what appears to be backstory is actually future memory, completely reconfiguring the emotional meaning of the narrative. Similarly, Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” withholds crucial information about Amy’s past actions and psychological makeup, creating shocking revelations that force readers to reevaluate everything they’ve understood about the story.

This technique requires tremendous discipline. Writers must know precisely what they’re withholding and why, resist the temptation to explain too soon, and ensure that the revelation isn’t merely surprising but meaningfully reshapes the narrative. The most effective delayed disclosures don’t just solve mysteries—they deepen them, transforming simple questions of “what happened?” into more complex questions of “what does it mean?”

Wounds That Shape Worldviews

Identifying your character’s core psychological injury

Every compelling character carries a core psychological injury—a fundamental wound that has shaped their beliefs about themselves and the world. This isn’t simply the worst thing that ever happened to them but the formative experience that altered how they process all subsequent experiences. For Bruce Wayne, the murder of his parents isn’t just tragic but identity-defining—it transforms his understanding of justice, power, and his own purpose.

The most effective core wounds share several characteristics. First, they occur at developmentally vulnerable moments when the character is forming fundamental assumptions about the world. Second, they involve a violation of the character’s existing worldview (the world was safe, then suddenly it wasn’t). Third, they create a specific adaptive response that made sense for survival then but creates limitations now.

These injuries rarely exist in isolation—they’re usually embedded in larger systems of family dynamics, cultural contexts, or historical circumstances. The injury might be personal (rejection by a parent), interpersonal (betrayal by a loved one), communal (discrimination or marginalization), or existential (witnessing senseless violence). What matters is how this specific wound created the lens through which the character now views all experience.

How unresolved trauma creates consistent yet complex reactions

Characters with well-developed psychological injuries don’t respond simplistically to triggers but show complex, layered reactions that may seem contradictory until we understand their internal logic. A character abandoned in childhood might simultaneously fear intimacy while desperately seeking connection, manifesting as behavior that pushes people away followed by frantic attempts to pull them back.

These reactions follow what therapists call “trauma logic”—responses that made perfect sense in the original wounding context but create problems in current situations. A character who learned to lie to avoid an abusive parent’s anger might continue this pattern in adult relationships where honesty is needed. These aren’t character flaws but survival adaptations that have outlived their usefulness.

The richest character development emerges from this tension between the consistency of trauma responses and the character’s growing awareness of their limitations. We see this in “The Queen’s Gambit” as Beth Harmon’s chess brilliance and her self-destructive tendencies both stem from the same childhood experiences—creating a character who is utterly consistent in her inconsistency, making her growth meaningful when it finally comes.

The Inevitable Collision Course

Crafting histories that make current conflicts feel unavoidable

When backstory and plot feel truly integrated, the central conflicts of your narrative seem not just likely but inevitable. The character’s specific history has created vulnerabilities, desires, or blind spots that make them uniquely susceptible to or prepared for the story’s central problem. This doesn’t remove tension but enhances it—readers sense the character is on a collision course with destiny.

In Sally Rooney’s “Normal People,” Marianne and Connell’s class differences and family histories create relationship patterns that feel inevitable given their specific wounds and defensive mechanisms. Their backstories don’t just explain their communication failures but actively generate them. Similarly, in “Breaking Bad,” Walter White’s history of feeling undervalued and emasculated makes his transformation into Heisenberg feel like the fulfillment of long-dormant potential rather than an arbitrary character shift.

This inevitability works best when the character’s backstory puts them at cross-purposes with themselves—when their conscious desires conflict with unconscious needs created by past wounds. A character might consciously want stable love while unconsciously seeking to reproduce familiar relationship dynamics, even destructive ones. This internal conflict creates stories where characters are authentic in their contradictions.

Establishing patterns that payoff in present storylines

Powerful backstories establish psychological or behavioral patterns that will be tested, broken, or fulfilled in the present narrative. These aren’t simply repeated behaviors but consistent responses to core triggers that will inevitably arise during the story’s central conflict. When developed skillfully, these patterns create deeply satisfying narrative payoffs as characters either transcend their histories or succumb to them.

Consider how in “The Haunting of Hill House,” each sibling’s present dysfunction directly reflects their specific experience in the house—creating different manifestations of similar trauma. The series establishes these patterns early, showing how childhood experiences shaped adult coping mechanisms, then pays them off as each character must confront specific aspects of their past to heal in the present.

The most sophisticated pattern establishment creates both obstacles and unexpected strengths. A character’s backstory-influenced behaviors might initially block their progress toward their goal but later provide unique resources for overcoming challenges. This transforms backstory from deterministic limitation into potential source of redemption or transcendence, creating narratives where characters neither escape their histories entirely nor remain trapped by them.

Beyond Villain Origin Stories

Building histories that invite empathy without excusing actions

The difference between simplistic villain origin stories and nuanced antagonist backstories lies in moral complexity. Simplistic approaches suggest direct causality: bad things happened, therefore the character does bad things. More sophisticated backstories reveal how understandable human responses to suffering can evolve into destructive choices through a series of small capitulations, environmental reinforcement, and gradual moral compromise.

Killmonger in “Black Panther” exemplifies this approach. His backstory—the murder of his father, abandonment by his homeland, and experience of racial oppression—makes his rage comprehensible without justifying his methods. The film invites viewers to recognize the legitimacy of his grievances while still condemning his willingness to inflict similar suffering on others. His history explains but doesn’t excuse.

This approach requires refusing both demonization and absolution. The antagonist’s backstory should reveal how they’ve arrived at a worldview that makes their actions logical within their moral framework. The gap between understanding their perspective and endorsing their actions creates the moral tension that elevates antagonists from obstacles to complex ethical challenges for protagonists and readers alike.

The delicate balance between understanding and judgment

The most compelling antagonist backstories maintain tension between empathy and accountability. They invite readers to understand the psychological mechanisms that shaped the character while still holding them responsible for their choices. This balance acknowledges that while past suffering explains present behavior, it doesn’t remove moral agency.

“Wicked” accomplishes this brilliantly by revealing Elphaba’s experiences of prejudice and marginalization without suggesting these hardships predestined her villainy. Instead, the narrative shows how similar wounds can lead to different outcomes through the parallel character of Glinda. The contrast emphasizes that while circumstances shape options, individuals still choose responses.

This approach creates space for redemption without guaranteed absolution. When antagonists’ backstories reveal unhealed wounds rather than innate evil, narratives can explore whether recognition of these wounds might lead to different choices—without suggesting that understanding automatically erases consequences. The most nuanced stories maintain that tension until the end, recognizing that comprehending someone’s pain doesn’t obligate forgiving their infliction of it on others.

Revealing Without Info-Dumping

Dialogue that naturally unveils the past

Skillful revelation of backstory through dialogue occurs when characters have authentic reasons to discuss the past—not for the reader’s benefit but for their own purposes within the scene. This might happen through conflict (accusations referencing past betrayals), intimacy (vulnerable sharing of formative experiences), or necessity (information needed to address a current problem).

The most natural backstory dialogue emerges from power dynamics between characters. Information is revealed because someone needs something: forgiveness, understanding, help, or leverage. In Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go,” revelations about the characters’ origins come through conversations between students with different levels of knowledge, creating a realistic context for exposition while maintaining narrative tension.

Effective backstory dialogue also reveals character through what remains unsaid or how information is framed. A character might minimize traumatic experiences, rationalize past behavior, or demonstrate selective memory—all revealing their relationship to their own history. This approach transforms exposition into characterization, making backstory active rather than passive.

Environmental triggers and meaningful objects as memory portals

Physical environments and objects provide organic entry points to character memory without requiring explicit exposition. A character returning to a childhood home might notice the height markings on a doorframe, triggering specific memories. A found photograph might reveal family dynamics through who stands where, who’s smiling, whose hand rests on whose shoulder.

These memory portals work because they reflect how human memory actually functions—associatively rather than chronologically. In “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy, the man’s memories surface through encountered objects that have lost their original purpose in the post-apocalyptic landscape, creating poignant contrasts between past and present while revealing his history without extended flashbacks.

Objects work especially well when they carry ambiguous or evolving significance. A keepsake might initially seem to represent one aspect of a character’s past only to reveal deeper meaning as the narrative progresses. This layered approach allows backstory to unfold organically while creating mini-revelations that maintain reader engagement with the character’s history.

Flashbacks that earn their place in the narrative

Effective flashbacks function not as information delivery systems but as dramatic scenes that actively advance emotional understanding or plot development. They should create new questions even as they answer existing ones, maintaining narrative momentum rather than pausing it. The flashback must reveal something that changes the reader’s understanding of present events in a crucial way.

Timing transforms flashback effectiveness. The most powerful flashbacks occur at moments of heightened emotion or significant decision points, when the intrusion of memory feels psychologically authentic rather than structurally convenient. In “Beloved,” flashbacks to Sethe’s escape from slavery emerge as her present safety dissolves, reflecting how trauma resurfaces during periods of threatened security.

The transition into and out of flashbacks also affects their integration. Rather than announcing temporal shifts, skilled writers use sensory bridges—a sound, smell, or image that exists in both timeframes—to create seamless movement between past and present. These transitions emphasize continuity of experience rather than separation, underscoring how the past continues to live within characters.

The Evolving Nature of Personal History

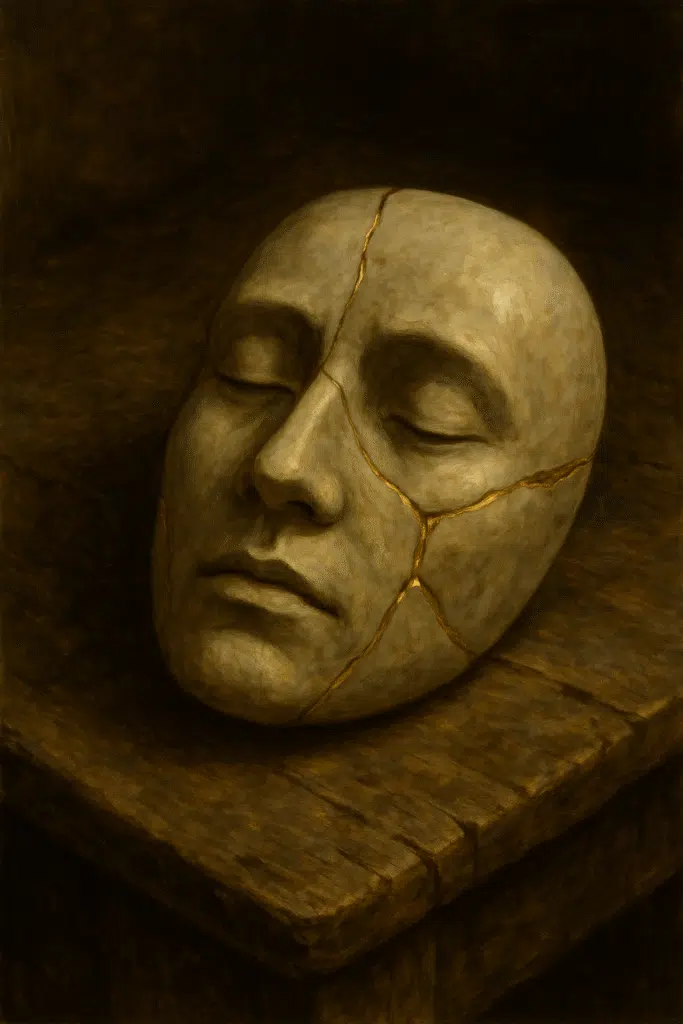

How character growth recontextualizes past events

As characters develop new perspectives, their understanding of their own histories transforms—not changing what happened but reframing its meaning and significance. This evolution mirrors real human psychological development, where growth often involves reinterpreting formative experiences through more mature understanding.

In “Educated” by Tara Westover, the narrator’s perspective on her childhood shifts dramatically as education provides new frameworks for understanding her family dynamics. What once seemed normal reveals itself as abusive; what appeared to be protection unmasks as control. The events remain the same, but their meaning transforms completely through expanded context and psychological development.

This recontextualization creates particularly powerful moments when characters revisit physical locations or reconnect with people from their past, experiencing the cognitive dissonance between memory and present perception. These encounters often serve as measuring sticks for growth, showing how the character has evolved while acknowledging the continuing influence of formative experiences.

When the villain of your memory becomes something more complex

One of the most profound forms of backstory evolution occurs when characters reassess people who hurt them, moving from simplistic vilification to recognition of complexity. This isn’t about excusing harm but about developing the emotional maturity to see beyond binary categories of hero and villain into more nuanced understanding of human limitation.

In “The Glass Castle,” Jeannette Walls’ portrayal of her father evolves from childhood worship through teenage resentment into adult acknowledgment of his simultaneous brilliance and brokenness. This progression doesn’t minimize his failures but contextualizes them within his own unresolved wounds, creating a portrait that honors both the damage he caused and the love he offered.

This evolution often creates the emotional climax of character-driven narratives—not when external conflicts resolve but when internal understanding transforms. The moment a character recognizes the humanity of someone they’ve demonized in memory often represents their most significant growth, marking the transition from reactive patterns based on past wounds to conscious choices based on present understanding.

Backstory in Different Narrative Forms

Short stories versus series-length arcs

Short stories require economical approaches to backstory, often revealing character history through implication rather than explicit statement. A character’s reaction to a situation might suggest past experience; a single telling detail might evoke an entire history. Alice Munro exemplifies this approach, using precise moments and gestures to suggest depths of experience without extensive explanation.

This constraint becomes an advantage by forcing writers to identify only the most essential elements of character history—the specific wounds or experiences that directly influence the story’s central conflict. In Raymond Carver’s minimalist stories, backstory often appears through brief references that carry disproportionate emotional weight precisely because they’re not elaborated upon.

Series-length narratives allow backstory to unfold gradually, with initial mysteries developing into complex revelations across multiple installments. “Mad Men” demonstrates this approach, slowly unveiling Don Draper’s history while using each revelation to recontextualize earlier behaviors. This extended format permits layered backstory where each revelation contains further mysteries, maintaining engagement across seasons.

Visual versus written mediums

Visual storytelling requires translating internal history into external signifiers—costume choices that reflect class background, physical environments that reveal personal history, or body language that suggests past trauma. “Parasite” uses the vertical geography of Seoul and architectural contrasts to communicate the characters’ socioeconomic backstories without explicit exposition.

While written narratives can directly access character thoughts and memories, visual mediums must find creative alternatives. Flashbacks in film often employ distinctive visual styles (different color grading, aspect ratios, or film grain) to signal temporal shifts. Television series like “The Handmaid’s Tale” use consistent visual language—shifting to warmer colors and looser camera movements for pre-Gilead scenes—to orient viewers in the character’s timeline.

Interactive mediums like video games offer unique opportunities for backstory engagement by allowing players to discover character history through exploration. Games like “What Remains of Edith Finch” or “Gone Home” transform backstory discovery into active gameplay, with players piecing together family histories through environmental storytelling and found objects—making revelation participatory rather than passive— just as strong worldbuilding can embed history into physical space..

When Less History Creates More Mystery

Characters who benefit from minimal backstory

Some characters derive their narrative power specifically from limited backstory. Anton Chigurh in “No Country for Old Men” embodies unstoppable, amoral force precisely because his origins remain unexplained. His lack of conventional motivation makes him terrifying—he operates according to principles outside normal human psychology, and this incomprehensibility becomes his defining feature.

Minimal backstory works particularly well for characters who function as representatives of larger forces rather than fully individualized personalities. The Joker in “The Dark Knight” gains power from his multiple conflicting origin stories, embodying chaos as a principle rather than psychology. His famous line, “If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice,” explicitly acknowledges how absence of definitive history enhances his archetypal function.

This approach requires careful balance—providing enough specificity for the character to feel concrete while withholding information that would diminish their symbolic resonance. The most successful minimally-backstoried characters often have distinctive behaviors, speech patterns, or philosophical perspectives that create depth without conventional history.

The power of the unknown in certain narrative contexts

Mystery, horror, and thriller genres often deliberately withhold backstory to maintain tension or preserve ambiguity. H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror deliberately avoids explaining the origins of its monstrosities, understanding that unexplained phenomena generate more profound fear than those fully comprehended. The unknown becomes a narrative tool rather than a gap to fill.

This approach works when the point of the narrative is precisely the unknowability of others or the limitations of human understanding. In films like “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the alien intelligence remains deliberately unexplained because its incomprehensibility is thematically central—the narrative is about the boundaries of human cognition and the vastness of what lies beyond it.

The most sophisticated use of unknown backstory creates productive ambiguity rather than simple frustration. When David Lynch refuses to fully explain events in “Mulholland Drive,” he’s not being arbitrarily withholding but creating space for multiple interpretations that reflect the film’s themes of identity fragmentation and the constructed nature of narrative itself. The backstory isn’t missing—it’s deliberately multivalent.

The stories that linger with us rarely happen in a narrative vacuum—they emerge from the rich soil of a character’s lived experience. As you lay the foundations of your fictional worlds, remember that backstory isn’t merely historical context; it’s the invisible current flowing beneath every scene, every line of dialogue, every moment of decision. The most compelling characters carry their histories not as baggage to be explained, but as the very lens through which they interpret and react to the world around them. When we understand that the past doesn’t just precede the story but actively shapes it, we begin to write narratives that feel not just constructed, but discovered—as though these characters existed long before we put them on the page, and will continue existing long after the final chapter closes.