From the Private Journals of Sir Alaric Veyrand

4th Day of Amberfell, Year 2742 of the High Crown

The transition from Marridge’s bustling agricultural terraces to Dellfold’s hushed valley sanctuary proved more dramatic than I had anticipated. As Quill and I descended through morning mist that seemed to rise from the earth itself, I found myself entering what could only be described as a pocket of Eden carved into the highland’s harsh landscape.

The sheltered valley revealed itself gradually through veils of vapor that clung to ancient stone walls, each terrace level emerging like a revelation of careful human partnership with natural protection. Where Marridge had impressed me with its mathematical precision applied to challenging terrain, Dellfold whispered of gentler mastery—the art of coaxing healing from highland soil through patience that spanned generations.

“Sir Alaric,” Herb Keeper Sage Willowbough greeted me at the valley’s entrance, her weathered hands already stained with the morning’s work among the medicinal plots. A woman of perhaps sixty years, she moved through her domain with the unhurried confidence of someone whose expertise had proven itself through decades of successful healing. “Welcome to our sanctuary. I trust the descent proved illuminating?”

Indeed it had. From aerial observation, the valley’s arrangement had seemed almost random—scattered greenhouse structures, irregular planting areas, pathways that curved without apparent purpose. Yet approaching on foot revealed design that worked with natural protection rather than imposing geometric order upon resistant landscape.

“The terracing follows different principles than Marridge’s agricultural systems,” I observed while following Sage Willowbough along pathways that meandered between carefully tended plots.

“Different purposes require different approaches,” she replied. “Marridge maximizes production through mathematical optimization. We cultivate healing through understanding what each plant requires for optimal potency.”

The first greenhouse complex proved to be an architectural marvel whose sophistication I had underestimated during previous glimpses. Built into the valley’s natural contours using highland granite and crystalline panels, the structures created controlled environments that extended growing seasons while maintaining plant varieties that could not survive exposed highland conditions.

“The Feverfew requires precise temperature control during its flowering period,” Sage Willowbough explained while adjusting ventilation systems that managed air circulation with mechanical precision. “Three degrees too warm and the active compounds degrade. Too cool and the flowers never develop proper potency.”

I examined the greenhouse’s environmental controls, noting engineering sophistication that rivaled any academic botanical facility. Temperature regulation, humidity management, air circulation, and light control had been integrated into a single system that maintained optimal growing conditions through seasonal variations that would challenge contemporary horticultural science.

“Highland healing requires reliability that academic theory cannot afford to compromise,” she replied when I commented on the precision. “When winter isolation might prevent access to external medical supplies, cultivation precision becomes survival necessity.”

Yet as morning progressed toward active garden work, I discovered that Dellfold’s botanical achievements served purposes beyond mere cultivation efficiency. The plant arrangements created environments where medicinal preparation integrated with spiritual practices that enhanced rather than competed with technical effectiveness.

“The Valleymint grows only here because the valley itself provides spiritual protection that the plant requires for proper development,” explained Garden Master Thorne Greenthumb, whose family had maintained these plots for four generations. “Physical cultivation techniques serve botanical requirements, but spiritual attention ensures the healing properties develop properly.”

The statement initially struck me as folklore, yet something in his matter-of-fact delivery suggested practical knowledge rather than mere tradition. The Valleymint plants certainly thrived in ways that my botanical understanding could not fully explain—their vigorous growth and unusual aromatic intensity indicated exceptional health despite growing conditions that should have been marginally adequate.

We spent the morning hours documenting plant varieties that challenged my understanding of highland botany. Species that academic classifications indicated should not coexist flourished in carefully arranged communities that seemed to enhance each other’s medicinal properties through proximity relationships that formal science had not identified.

“The Heartleaf requires companion planting with Stoneroot to develop proper digestive healing properties,” Thorne explained while demonstrating traditional planting arrangements. “Separate cultivation produces plants with minimal therapeutic value. Together, they create medicines that can resolve conditions no single herb could address.”

More intriguing still were the preparation methods that transformed highland plants into medicines of remarkable effectiveness. The Drying Sheds demonstrated preservation techniques that maintained medicinal potency through processing methods that balanced traditional wisdom with contemporary understanding of plant chemistry.

“Proper drying requires timing that coordinates plant harvest with atmospheric conditions that optimize preservation,” explained Plant Sage Ivy Rootfinder, the hamlet’s specialist in medicinal development. Her precise movements while handling delicate plant materials spoke to expertise refined through years of careful practice. “Temperature, humidity, air circulation—all must align with plant biology and seasonal rhythms for maximum therapeutic value.”

I found myself assisting with actual herb processing work, my hands learning to distinguish medicinal gradations through touch and scent that formal training had not prepared me to recognize. Rather than fumbling incompetence, I discovered genuine appreciation for work that required both theoretical understanding and practical sensitivity to plant materials.

“Root cutting should account for both fiber direction and seasonal potency variations,” I suggested while attempting to prepare Stoneroot according to traditional methods.

“Excellent foundation,” Ivy agreed while observing my technique. “Though you’ll want to adjust for this particular plant’s healing properties. Stoneroot develops maximum potency when cut during specific lunar phases—your timing is perfect, but the angle needs slight modification for optimal extraction.”

My academic knowledge provided useful starting points that practical experience enhanced. The healers appreciated systematic approaches that supported rather than replaced their traditional understanding, while I learned to adapt theoretical precision to plant materials that responded to environmental subtleties beyond mechanical measurement.

The afternoon brought education in the Plant Laboratory, a facility that combined traditional knowledge with careful experimentation. Rather than competing methodologies, I encountered collaborative approaches that served highland healing more effectively than either approach in isolation.

“The cultivation experiments follow systematic protocols that test traditional knowledge against measurable results,” Ivy explained while demonstrating research techniques that integrated scientific methodology with traditional plant wisdom. “Academic rigor enhances rather than replaces experiential understanding when properly applied.”

“Medicinal plant development requires patience that academic research schedules rarely accommodate,” I observed while documenting experimental protocols that extended across multiple growing seasons.

“Plants operate on their own timeline,” Ivy replied. “Cannot rush breeding programs to match scholarly publication deadlines. Highland healing values effectiveness over academic recognition.”

The day concluded with participation in traditional blessing ceremonies that combined practical plant preparation with spiritual practices serving community healing coordination. Rather than mere ritual, the physical act of blessing herbs proved to be applied meditation that enhanced preparation precision while ensuring community-wide coordination of medical supplies.

“The evening blessing connects individual plant preparation with collective healing needs,” Sage Willowbough explained while leading ceremonies that integrated spiritual practice with practical medicine. “Highland survival requires healing resources that individual effort alone cannot provide.”

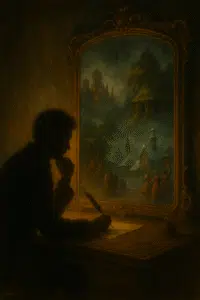

Walking back to the Healing House as stars emerged over the protected valley, I reflected on discoveries that had challenged academic assumptions about the relationship between scientific methodology and traditional healing. Dellfold had demonstrated that botanical knowledge could achieve remarkable sophistication while serving practical medical needs.

Quill preened his feathers while settling on his perch, clearly pleased with a day spent investigating something more gentle than Dornview’s harsh winds or Marridge’s demanding agricultural schedules. I suspect he appreciated the valley’s protection as much as I did—there’s something to be said for scholarly work that doesn’t require bracing against highland storms.

The gentle arts had revealed themselves as sophisticated integration of multiple knowledge systems that served highland healing through methods that formal education was only beginning to appreciate. Tomorrow would bring deeper investigation into the unique species that existed only in this protected valley, though tonight I found myself grateful for work that whispered rather than shouted its importance.

5th Day of Amberfell, Year 2742 of the High Crown

The morning brought me deeper into Dellfold’s hidden treasures, where Plant Sage Ivy Rootfinder had promised to show me species that existed nowhere else in the known world. “Isolation creates opportunity,” she had said the previous evening, and as we descended into the valley’s most protected cultivation areas, I began to understand the profound truth of that statement.

The path wound through sections of the herb gardens I had not explored yesterday, leading to greenhouse complexes that seemed to grow directly from the valley walls themselves. Here, the morning light filtered through crystalline panels in ways that created an almost ethereal quality to the air itself.

“The Valleymint is perhaps our greatest achievement,” Ivy explained as we approached a series of low, carefully tended beds. “Four centuries of selective cultivation in this specific microclimate have produced a plant that bears little resemblance to its highland ancestors.”

I knelt beside the beds, examining leaves that seemed to glow with internal vitality. Even without my lens of insight, the plant’s exceptional quality was evident—the aromatic oils so concentrated I could detect their complexity from arm’s length, the leaf structure more robust than any mint variety I had encountered in my travels.

“The medicinal properties?” I inquired while sketching the plant’s distinctive characteristics.

“Pain relief beyond anything we can achieve with traditional remedies. A single leaf, properly prepared, can ease the joint pain that plagues highland workers through our harsh winters.” She paused, her weathered hands touching the plants with obvious reverence. “More importantly, it grows only here. We’ve attempted cultivation in Kalene’s gardens, in Marridge’s terraces, even in controlled environments. The plants survive, but they lose their potency entirely.”

This fascinated me more than simple botanical rarity. “The valley itself somehow enhances the plant’s development?”

“We believe so. The soil composition, the specific pattern of morning mist, the way sound echoes off these particular stone walls—something about this exact location creates conditions the Valleymint requires.” Ivy led me deeper into the cultivation area, where I noticed other plants displaying similar exceptional characteristics.

The Heartmend showed leaves with unusual silvering that I had never encountered in lowland varieties. When properly prepared, according to Ivy, it could strengthen weak hearts and steady irregular rhythms. The Dreamease produced flowers of such delicate beauty that I spent considerable time attempting to capture their essence in my sketches, yet their true value lay in providing peaceful sleep to those tormented by highland nightmares.

“Each species represents generations of careful selection,” Ivy continued as we moved between beds that seemed more like sacred gardens than practical cultivation areas. “But more than that—they represent partnership between human intention and natural possibility.”

We spent the morning documenting preparation methods that transformed these unique plants into medicines of remarkable effectiveness. In the Processing Hall, a stone building carved directly into the valley wall, I watched techniques that balanced scientific precision with what could only be called intuitive understanding.

“The timing matters as much as the method,” explained Master Preparer Rowan Stillhand, whose steady fingers worked with plant materials as a master craftsman might handle precious metals. “Valleymint harvested at dawn carries different properties than evening harvest. Storm-gathered leaves possess healing qualities that fair-weather plants cannot match.”

I found myself assisting with the delicate work of extracting essential oils, my academic training providing useful foundation while practical experience taught me subtleties no textbook had ever described. The scents alone created a complex symphony that seemed to clarify thought while calming anxiety.

“Your hands show natural sensitivity,” Rowan observed as I learned to test oil consistency through touch. “Many scholars rely too heavily on instruments for work that requires direct sensation.”

The comment struck me as both compliment and gentle correction. My tendency toward mechanical measurement, while valuable, sometimes prevented the immediate understanding that careful attention could provide.

The afternoon brought exploration of the Storage Caves, natural formations that Dellfold’s healers had adapted for preserving their precious medicines. Here, constant temperature and humidity created ideal conditions for maintaining potency through Highland’s extreme seasonal variations.

“The caves breathe with the earth itself,” explained Cave Keeper Gareth Deepwatch, whose family had maintained these storage areas for six generations. “Medicines stored here retain effectiveness for years, while surface storage might see them lose potency within months.”

Walking through chambers lined with ceramic vessels and wrapped bundles, I felt as though I had entered a treasury more valuable than any noble’s gold. Each container held healing potential that could ease suffering and save lives throughout the highland settlements.

“The preservation methods follow principles that formal pharmacy is only beginning to understand,” I noted while documenting storage techniques that achieved remarkable results through apparently simple methods.

“Simple in appearance, complex in application,” Gareth replied. “Temperature variation patterns, air circulation requirements, protection from moisture fluctuation—every detail matters when healing effectiveness depends on perfect preservation.”

Yet as afternoon progressed, I began to understand that Dellfold’s achievements extended beyond exceptional cultivation and preservation. The healers had created something approaching alchemy—the transformation of highland plants into medicines that seemed to possess almost magical effectiveness.

“The preparation rituals serve practical purposes,” Ivy explained when I inquired about the spiritual elements that accompanied technical procedures. “Focused attention during processing enhances medicine quality in ways that mechanical preparation cannot achieve.”

This integration of spiritual practice with botanical science fascinated me. The healers approached their work with reverence that seemed to enhance rather than compromise scientific effectiveness, creating medicines through methods that honored both plant biology and human consciousness.

We concluded the day with participation in evening processing sessions, where community members gathered to prepare medicines that would serve highland settlements throughout the coming season. Rather than individual work, this became collaborative creation that strengthened community bonds while ensuring medical supplies.

“Highland healing requires coordination that individual effort cannot provide,” Ivy observed as we worked together preparing Valleymint extracts. “These sessions connect individual skill with collective need.”

I found genuine satisfaction in contributing meaningfully to work that would ease suffering throughout the highlands. My systematic documentation skills proved valuable for maintaining preparation records, while I learned traditional techniques that achieved results my formal training had never anticipated.

As evening settled over the protected valley, I walked the garden paths alone, reflecting on discoveries that challenged fundamental assumptions about the relationship between natural environment and human cultivation. Dellfold had demonstrated that isolation, rather than limiting development, could create opportunities for achievements impossible under normal conditions.

The valley’s unique plants represented more than botanical curiosities—they embodied the potential for human partnership with natural forces to create healing that transcended what either could achieve alone. The healers had not conquered their environment but had learned to dance with it, creating conditions where exceptional medicine could flourish.

Tomorrow would bring departure from Dellfold’s gentle sanctuary toward Byrnden’s harsh quarries, a transition that promised to test my adaptability to highland extremes. Yet tonight brought peaceful satisfaction in understanding gained and work that mattered, knowledge that would serve healing throughout the highlands for generations to come.

The hidden wisdom of specialized cultivation had revealed itself as patient partnership between human intention and natural possibility, creating treasures that existed nowhere else because they required conditions that could only be found in this singular place.

6th Day of Amberfell, Year 2742 of the High Crown

The transition from Dellfold’s protected embrace to Byrnden’s exposed stone landscape struck me with physical force that left me momentarily speechless. One moment I stood among healing gardens where morning mist softened every edge, the next I faced raw highland granite thrust skyward in formations that spoke of geological violence stretching back to the world’s creation.

“Bit of a shock, that,” observed Quarry Master Garren Stonewright as he noted my stunned expression. A man built like the stone he worked—broad, weathered, uncompromising—he had awaited our arrival at the hamlet’s edge with the patient amusement of someone accustomed to visitors’ reactions. “Most folk need a moment to adjust. Valley softness doesn’t prepare you for what honest rock looks like.”

Indeed it did not. Where Dellfold had whispered its secrets through gentle cultivation, Byrnden shouted its truths through exposures of stone that revealed the highland’s very bones. The rocky outcroppings rose in dramatic formations that challenged both eye and understanding, their surfaces bearing the scars of countless years of careful extraction.

“The Ancient Quarry,” Garren continued, gesturing toward formations that dominated the hamlet’s northern approach, “has provided building stone for highland construction since before written records began. Possibly since before men learned to write at all.”

Following him along paths that seemed to have been carved from living rock, I found myself entering what could only be described as a sculptor’s workshop on the scale of mountains. Yet where an artist might work marble or bronze, these craftsmen shaped the very foundation material upon which highland civilization rested.

The quarry faces revealed stone of exceptional quality—granite so fine and uniform that my geological training immediately recognized its suitability for demanding construction applications. Yet what impressed me more than the material itself was the evidence of human skill applied across centuries to extract it without compromising either quality or structural integrity.

“Tool marks show at least twelve distinct periods of extraction,” I observed while examining surfaces that bore the evidence of different cutting techniques. “Some of these appear ancient beyond easy dating.”

“Aye, the old workers knew their business,” Garren agreed, his callused hands tracing cuts that might have been made yesterday or a thousand years past. “Stone quality like this doesn’t occur by accident. Takes skill to extract it without damage, more skill to know which sections will serve different construction purposes.”

We spent the morning examining various quarry faces, each revealing different aspects of the stone-working knowledge that had been refined across generations of highland builders. Some sections showed evidence of careful selection for specific architectural applications—foundation stones that required maximum strength, decorative elements that demanded fine grain structure, massive blocks intended for defensive construction.

“The grading system follows principles that contemporary architecture has not systematized,” I noted while documenting stone quality variations that experienced eyes could detect but formal training had not prepared me to recognize.

“Book learning comes after practical necessity,” Garren replied matter-of-factly. “Highland builders learned stone grading through trial and error across centuries. Your architectural theory might explain why certain stones work better for specific purposes, but it won’t teach you to spot quality granite from across a quarry.”

The observation proved both humbling and instructive. My academic training provided useful vocabulary for describing what I observed, but the quarrymen possessed direct knowledge that could assess stone quality through brief examination that would require extensive testing using formal methods.

As morning progressed toward active quarrying operations, I discovered that Byrnden’s stone-working represented integration of practical skill with spiritual practices that served both safety and quality purposes. The work was dangerous enough that spiritual protection seemed not merely traditional but genuinely necessary.

“Tool blessing ensures both sharp edges and steady hands,” explained Foundation Sage Aldric Bedrock, whose weathered face bore the particular gravitas that marked those who regularly faced mortal danger. “Stone-working kills careless men. Proper reverence keeps tools sharp and minds focused.”

I witnessed the tool blessing ceremony with growing appreciation for its practical functions. Rather than mere ritual, the careful examination and consecration of cutting implements served as systematic safety inspection that could prevent equipment failure during dangerous extraction work.

“The blessing timing coordinates tool maintenance with optimal stone-cutting conditions,” Aldric continued while demonstrating the spiritual practices that preceded quarry work. “Highland stone responds differently to cutting depending on seasonal conditions, atmospheric pressure, even time of day.”

This integration of spiritual practice with technical knowledge fascinated me. The quarrymen approached their dangerous work with reverence that enhanced rather than competed with practical safety measures, creating working conditions that honored both human limitations and stone’s inherent properties.

“Foundation meditation helps workers understand stone grain patterns before beginning extraction,” Aldric explained while leading me through the mental preparation that preceded actual cutting work. “Rushing stone-work leads to broken tools, wasted material, injured workers.”

The meditation proved more practical than mystical—a systematic process of observing stone characteristics, planning cutting sequences, and preparing for the physical demands of extraction work. Yet the spiritual framework created focused attention that enhanced rather than replaced technical skill.

The afternoon brought hands-on education when Garren suggested I assist with actual stone selection and preparation. Rather than another humbling encounter with my limitations, I found myself contributing meaningfully to work that required both theoretical understanding and practical judgment.

“Your geological training helps identify stone formation patterns,” Garren observed while I attempted to assess granite quality using formal criteria. “Though you’ll need to adjust academic categories to practical construction requirements.”

My mineralogical knowledge provided useful foundation for understanding stone composition and structural properties, while the quarrymen taught me to translate theoretical assessment into practical selection for specific building applications.

“Academic geology describes stone formation accurately,” I noted while learning to balance formal classification with practical evaluation. “Though it doesn’t address construction suitability directly.”

“Different purposes,” Garren agreed. “University geology seeks to understand how stone formed. Highland quarrying needs to know how it will perform when shaped into foundation blocks.”

As afternoon progressed, I began to understand that Byrnden’s achievements represented integration of geological knowledge with practical craftsmanship that served highland construction through methods that individual academic disciplines could study but might not achieve independently.

The day concluded with examination of finished stone products—blocks cut and shaped for specific construction projects throughout the highland settlements. Each piece demonstrated craftsmanship that balanced efficient extraction with architectural requirements that demanded precision.

“The foundation stones for Kalene’s new granary,” Garren explained while showing me massive blocks prepared for transport. “Cut to exact specifications, shaped for optimal weight distribution, finished for weather resistance. Highland construction demands stone-work that will endure centuries of highland storms.”

Walking among finished products that would soon become permanent parts of highland architecture, I reflected on the essential but often overlooked role that quarrying played in highland civilization. Without Byrnden’s skilled extraction and preparation, the sophisticated architecture I had documented throughout the highlands could not exist.

The evening brought rest in the Mason’s Workshop, a stone building that served as both accommodation and informal gathering place for the hamlet’s workers. Shared meals and conversations revealed intellectual depth to stone-working that extended beyond manual craftsmanship to encompass understanding of geological principles, architectural requirements, and construction engineering.

“Stone teaches patience,” observed Master Cutter Willem Sharpsight as we discussed the relationship between material properties and construction applications. “Cannot rush quality granite. Must work with stone’s natural characteristics rather than forcing it to conform to arbitrary requirements.”

The philosophy extended beyond quarrying technique to encompass approaches to knowledge that valued direct experience over theoretical abstraction. These craftsmen understood their materials through intimate contact that formal education could supplement but not replace.

Tomorrow would bring investigation of the Ancient Quarry’s deepest sections, where evidence of highland stone-working stretched back through centuries or possibly millennia. If today’s examination of current operations had revealed such unexpected sophistication, what revelations might await in the archaeological evidence of stone-working’s ancient origins?

The night brought the peculiar silence that settles over highland stone country—not the absence of sound but its absorption into granite formations that seemed to drink noise from the air itself. Resting among craftsmen whose work provided the literal foundations for highland civilization, I found myself appreciating skills that enabled everything else while rarely receiving recognition their importance deserved.

7th Day of Amberfell, Year 2742 of the High Crown

Dawn found me standing before the entrance to Byrnden’s active quarry, where Foundation Sage Aldric Bedrock waited with the quiet gravity of a man about to conduct sacred work in a dangerous place. The morning air carried the metallic scent of stone dust and the distant ring of hammers already at work in the quarry’s depths.

“Foundation meditation comes first,” Aldric said simply, settling himself on a flat boulder that overlooked the quarry operations. “Stone-work begins in the mind, Sir Alaric. The hands merely follow what the understanding has prepared.”

I joined him on the stone seat, initially uncertain what meditation might accomplish before physical labor. Yet as we sat in silence watching the morning light reveal the quarry’s complex geometry, I began to understand that this was not mystical practice but practical preparation for work that demanded absolute attention.

“Feel the stone beneath you,” Aldric instructed quietly. “Granite holds the earth’s memory. Listen to what it tells you about its grain, its stress patterns, the places where it wants to break cleanly and the places where it will fight you.”

Closing my eyes and focusing my attention on the rock supporting my weight, I discovered that the stone did indeed seem to communicate—not through supernatural means, but through subtle variations in texture, temperature, and the way sound resonated through the material. My geological training had taught me to analyze such characteristics, but this meditation encouraged direct sensory awareness that bypassed academic categories.

“The morning’s work will require cutting foundation blocks for the new bridge at Thornvale,” Aldric continued, his voice barely above a whisper. “Heavy stones that must bear weight for generations. Feel in your mind the grain patterns that will give such stones their strength.”

The exercise proved surprisingly effective at focusing attention on the specific requirements of the day’s labor. Rather than approaching stone-cutting as generic manual work, the meditation prepared me to engage with particular materials for specific purposes that demanded understanding their individual characteristics.

When we finally descended into the quarry proper, I carried with me awareness of the granite’s properties that direct examination alone could not have provided. The stone seemed less like inert material and more like a partner whose cooperation would be necessary for successful work.

“Your academic training serves you well here,” observed Master Cutter Willem Sharpsight as I examined potential cutting sites using both formal geological assessment and the intuitive awareness the meditation had cultivated. “Though you’ll want to trust your hands as much as your instruments.”

The morning’s instruction proved both humbling and enlightening. Where I had expected to fumble with tools designed for skilled craftsmen, I found myself learning techniques that built upon rather than dismissed my theoretical knowledge. The quarrymen appreciated systematic approaches that enhanced rather than replaced their practical expertise.

“Tool placement should account for grain direction and potential stress concentration,” I suggested while positioning a cutting chisel according to principles I had learned from structural engineering texts.

“Good foundation,” Willem agreed, guiding my hands to adjust the angle slightly. “Though granite grain runs differently than your books might indicate. Feel how the stone wants to split—work with its natural preferences rather than forcing arbitrary cuts.”

My engineering knowledge provided useful starting points that practical experience refined. The craftsmen valued systematic thinking that supported their intuitive understanding, while I learned to adapt theoretical precision to materials that possessed individual characteristics requiring flexible response.

The physical demands of quarry work tested limits I had not anticipated. My noble upbringing had included sufficient physical training to handle expedition work, but sustained stone-cutting required stamina and strength that scholarly life had not developed. Yet rather than mocking my limitations, the quarrymen adjusted their instruction to my capabilities while ensuring I contributed meaningfully to the work.

“Pace matters more than strength in stone-work,” Willem explained as I learned to maintain cutting rhythm despite burning muscles. “Consistent steady work outlasts forceful effort that cannot be sustained. Highland quarrying succeeds through persistence rather than dramatic displays.”

The observation applied to more than physical technique. The quarrymen approached their dangerous work with methodical care that prioritized safety and quality over impressive demonstrations of skill. Each cut required planning, each tool change demanded attention, each movement needed consideration of how it affected overall progress.

“Stone-working teaches patience through necessity,” noted Apprentice Cutter Donal Steadyhand, a young man whose careful movements suggested natural aptitude refined through careful instruction. “Cannot rush quality granite. Hurried work produces broken tools, wasted stone, sometimes injured workers.”

As afternoon progressed, I began to understand that the spiritual dimensions of stone-working served practical functions that enhanced rather than competed with technical skill. The reverent attention demanded by traditional practices created working conditions that improved both safety and effectiveness.

“The blessing timing coordinates spiritual preparation with optimal cutting conditions,” Aldric explained during our midday rest period. “Highland stone responds differently to working depending on atmospheric pressure, seasonal moisture content, even time of day. Proper reverence ensures we work when conditions favor success.”

The integration fascinated me. Rather than separate domains competing for attention, spiritual practice and technical skill reinforced each other through understanding that effective stone-work required harmony between human intention and material properties.

“Foundation ceremonies connect individual craftsmanship with community construction needs,” Aldric continued while demonstrating blessing techniques that preceded afternoon’s more demanding cutting operations. “Highland survival requires stone-work that serves collective building requirements rather than personal achievement.”

The afternoon brought participation in cutting foundation blocks for Thornvale’s new bridge—massive stones that would bear significant structural loads for decades or centuries. The responsibility of contributing to infrastructure that would serve highland communities added weight to work that already demanded careful attention.

“Bridge foundation requires granite with specific strength characteristics,” Willem explained while selecting stones for our cutting operations. “These blocks will support spanning structures over Thornvale Gap during spring flood conditions. Inadequate stone means bridge failure and possible loss of life.”

The reminder that our work carried consequences beyond immediate craftsmanship enhanced the already serious attention that stone-cutting demanded. Each cut needed consideration not only for immediate success but for long-term structural performance under challenging conditions.

Yet despite the weighty responsibility, I found genuine satisfaction in contributing to essential infrastructure that would serve highland communities. My systematic documentation skills proved valuable for maintaining cutting records that tracked stone quality and preparation methods, while I learned traditional techniques that achieved results formal engineering training had not anticipated.

“Academic engineering provides useful frameworks for understanding structural requirements,” I noted while recording specifications that balanced formal calculations with practical stone assessment. “Though traditional selection methods often achieve superior results through direct material evaluation.”

“Different tools for different purposes,” Willem agreed. “University calculations help predict structural performance. Highland stone-work ensures the predictions prove accurate through material selection that formal analysis alone might miss.”

The day concluded with blessing ceremonies that consecrated finished foundation blocks for their intended service. Rather than mere ritual, the spiritual practices served as final quality inspection that ensured stones met both technical and spiritual requirements for structural service.

“Blessed stones carry community intention as well as structural strength,” Aldric explained while leading blessing ceremonies that connected individual craftsmanship with collective construction needs. “Highland building succeeds through understanding that structures serve communities rather than individual builders.”

Walking back to the Mason’s Workshop as evening light painted the quarry walls in golden tones, I reflected on discoveries that had challenged academic assumptions about the relationship between manual craftsmanship and intellectual understanding. Byrnden’s stone-workers had demonstrated that practical skill could achieve sophistication equal to formal engineering while serving essential community needs through approaches that honored both material properties and human limitations.

The evening brought shared meals and conversations that revealed philosophical depths to stone-working that extended beyond construction technique to encompass ways of understanding that connected individual effort with community survival. These craftsmen understood their work as essential service that enabled highland civilization through skills that formal education was only beginning to appreciate.

“The foundation knowledge passes through hands rather than books,” Willem observed while discussing the transmission of stone-working expertise across generations. “Cannot learn granite behavior through reading alone. Requires direct contact with materials that teach through resistance as much as cooperation.”

Resting among craftsmen whose work provided literal foundations for highland architecture, I found myself appreciating the dignity of essential labor that enabled everything else while rarely receiving recognition proportionate to its importance. Tomorrow would bring investigation of the Ancient Quarry’s deepest archaeological sections, but tonight brought satisfaction in understanding gained and work that mattered.

The maker’s touch had revealed itself as integration of knowledge systems that served highland construction through methods that honored both practical necessity and spiritual awareness. Stone-working had taught me that expertise could take forms that formal education was only beginning to recognize, much less properly value.

8th Day of Amberfell, Year 2742 of the High Crown

The descent into the Ancient Quarry’s deepest sections began before dawn, when morning mist still clung to the stone faces and the air carried that peculiar stillness that marks places where human labor has shaped landscape across vast spans of time. Quarry Master Garren and Foundation Sage Aldric had insisted on the early start—the lower reaches, they explained, revealed their secrets best in the gentle light of morning.

“Down here, you’ll see the true age of highland stone-working,” Garren said as we followed a winding path that descended past increasingly ancient quarry faces. “These sections haven’t been actively worked in living memory, but the evidence of old hands remains clear for those who know how to read it.”

The path led us past extraction sites that seemed to step backward through time with each level of descent. Where yesterday’s work had shown me modern quarrying techniques refined through generations of practice, these deeper sections revealed evidence of stone-working that stretched back through centuries, possibly millennia.

“Tool marks tell the story,” Aldric observed, his weathered hands tracing cuts that had been made when his grandfather’s grandfather was yet unborn. “Different periods, different techniques, but always the same understanding of how to work with stone rather than against it.”

I examined the ancient cutting marks with my lens of insight, noting the remarkable preservation that highland granite provided for evidence of human skill. Some cuts showed the precise geometry of metal tools that could have been made yesterday. Others bore the distinctive patterns of techniques I had encountered only in archaeological sites dating to the earliest periods of organized civilization.

“The continuity staggers me,” I murmured while documenting tool marks that spanned what might have been millennia of continuous extraction. “Bronze age cuts beside iron tool work, classical techniques adjacent to contemporary methods.”

“Aye, the quarry never truly sleeps,” Garren replied with obvious satisfaction. “Each generation finds what it needs here, learns from what came before, leaves evidence for those who follow. Stone remembers everything, Sir Alaric. Holds the memory of every hand that’s shaped it.”

As we descended deeper into sections that showed increasingly ancient work, I found myself facing evidence of technical sophistication that challenged assumptions about primitive stone-working techniques. The oldest cuts demonstrated precision that rivaled contemporary quarrying, achieved through methods that left subtle traces of extraordinary skill.

“These earliest sections show extraction techniques that formal archaeology has not adequately documented,” I observed while examining cuts that seemed almost impossibly precise for their apparent age. “The tool control required for such work suggests knowledge systems that academic study has underestimated.”

“Knowledge that passes through hands rather than books,” Aldric said quietly. “Each master teaches apprentices not just technique but understanding. The wisdom accumulates across generations, preserved in practical skill rather than written records.”

The statement struck me with unexpected force. Here was evidence of cultural continuity that spanned enormous periods of time, preserved not through academic institutions or written documentation but through direct transmission of practical knowledge from master to apprentice across countless generations of highland stone-workers.

“The geological implications fascinate me equally,” I continued while examining stone formations that revealed both natural processes and human selection criteria. “The quarry site was chosen with understanding of granite formation that contemporary geology confirms but could not have improved upon.”

The ancient quarrymen had selected this location for reasons that my formal training could analyze but not surpass. The stone quality remained exceptional throughout the deepest sections, indicating that whoever first established extraction here possessed geological knowledge that guided them to formations of remarkable consistency and structural integrity.

We spent the morning exploring sections that revealed the quarry’s development across vast periods of human occupation. Each level showed evidence of different periods adapting extraction techniques to their specific needs while building upon foundations established by previous generations.

“The continuity teaches patience,” Garren observed as we examined transitions between different periods of work. “Highland survival requires thinking beyond individual lifetimes. Each generation’s labor serves those who follow as much as current needs.”

The observation resonated more deeply than simple quarrying philosophy. Standing in depths carved by hands that had turned to dust before recorded history began, I felt the weight of human persistence in the face of highland’s challenging environment. These ancient workers had established foundations—literal and metaphorical—that continued to serve communities across centuries.

“The spiritual dimensions seem as ancient as the technical work,” I noted while examining areas that showed evidence of blessing ceremonies or ritual observances spanning multiple periods of extraction.

“Stone-work has always required reverence,” Aldric replied matter-of-factly. “Dangerous occupation that serves essential community needs. Proper spiritual attention ensures both safety and quality, connects individual labor with collective survival.”

As afternoon light filtered down into the ancient sections, I began to understand that the quarry represented more than archaeological curiosity. It embodied principles of sustainable practice that had enabled continuous operation across periods that saw empires rise and fall while highland communities endured through persistent attention to essential needs.

“The sustainability impresses me as much as the technical achievement,” I reflected while documenting evidence of extraction practices that maintained stone quality without depleting the resource base. “Contemporary quarrying might learn valuable lessons from traditional approaches that enabled centuries of continuous operation.”

“Highland survival requires taking only what’s needed, using everything that’s taken, leaving resources for those who follow,” Garren explained with the authority of someone whose family had participated in this continuity across multiple generations. “Wasteful quarrying exhausts sites quickly. Careful extraction enables permanent occupation.”

The principles applied beyond stone-working to encompass approaches to resource use that enabled long-term community survival in challenging environments. The ancient quarrymen had achieved sustainability through understanding that connected immediate needs with long-term consequences in ways that contemporary practice was only beginning to rediscover.

As afternoon progressed toward evening, we climbed back toward surface levels, carrying with us evidence of human persistence that humbled my assumptions about cultural development and technological progress. The quarry’s deepest sections had revealed sophistication that challenged linear notions of advancement, suggesting instead that knowledge could achieve remarkable depths through sustained practical application across generations.

“The archaeological evidence suggests continuous cultural transmission spanning periods longer than most recorded history,” I noted while organizing documentation that recorded tool marks and extraction techniques across multiple millennia of human occupation.

“Highland culture endures through practical knowledge rather than written records,” Aldric observed with quiet pride. “Books burn, libraries crumble, but skills preserved in living hands pass from generation to generation without interruption.”

The evening brought reflection on discoveries that had transformed my understanding of cultural continuity and knowledge preservation. The Ancient Quarry had demonstrated that human communities could achieve remarkable persistence through dedication to essential practices that served collective needs across vast spans of time.

Walking back to the Mason’s Workshop as stars emerged over highland peaks that had witnessed millennia of human labor, I carried with me understanding that extended beyond archaeological curiosity to encompass principles of sustainable practice and cultural transmission that formal education was only beginning to appreciate.

The ancient foundations revealed themselves as more than structural achievements—they represented human persistence in the face of challenging environments, knowledge systems that enabled community survival through understanding that connected individual effort with collective endurance across generations.

Resting among contemporary craftsmen whose work continued traditions established before recorded history began, I found myself humbled by evidence of cultural achievement that measured success not through dramatic innovation but through persistent dedication to essential service. The highland stone-workers had achieved something approaching immortality through practical knowledge that enabled continuous community survival across periods that transformed civilizations while leaving highland foundations essentially unchanged.

Tomorrow would bring departure from Byrnden toward continued documentation of highland communities, but tonight brought contemplation of foundations both literal and metaphorical that had enabled everything else I had observed during my highland investigations. The ancient quarry had taught me that some achievements measured their significance not in years or decades but in millennia of persistent service to community needs.

The whispers of ancient stone had become testimony to human endurance, evidence that knowledge preserved through practical application could achieve continuity that surpassed the durability of the granite itself. Highland culture had revealed its deepest secret—survival through understanding that connected individual labor with collective persistence across time scales that humbled scholarly pretensions while inspiring profound respect for the patient work of generations.